Career Narrative

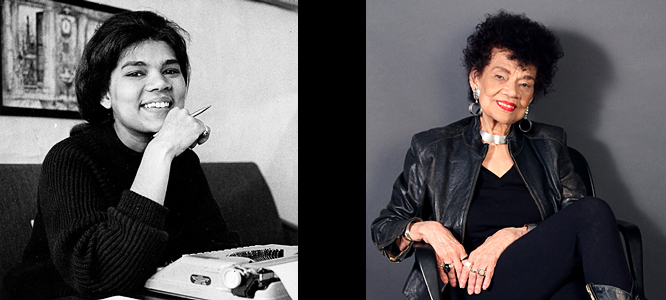

Lorraine O’Grady (1934-2024) was a concept-based artist and cultural critic widely regarded as a leading intellectual voice of her generation. Working across media and disciplines––including writing, photography, performance, curating, installation, and video––O’Grady continued to challenge artistic and cultural conventions through her incisive critique of the binary logic inherent in Western thought. She skillfully deployed the diptych form to refute and subvert both the “either/or” logic of Western philosophy and, by extension, the prevailing understanding around gender, race, and class. Over the course of her career, she advocated for an anti-hierarchical approach to difference that follows the reasoning of both/and. From her earliest work, Cutting Out the New York Times (1977), to more recent series like Family Portraits (2020), O’Grady expanded the possibilities of conceptual art and institutional critique through her profound explorations of hybridism and multiplicity. And in writings such as “Olympia’s Maid: Reclaiming Black Female Subjectivity,” an influential essay of cultural criticism published in 1992, O’Grady continued to shape the theoretical contours of a body of work that has been groundbreaking in its charting of the emergence of Black subjectivity in both artistic modernism and Western modernity as a whole.

O’Grady came to artmaking in the late 1970s after having achieved professional successes as a research economist, a literary and commercial translator, and a rock music critic. Her decision to become an art maker being due to the desire to produce work in service of her own ideas, O’Grady has stated that art “is the primary discipline where an exercise of calculated risk can regularly turn up what you had not been looking for.” Indeed, O’Grady’s strategies in Cutting Out the New York Times (1977) were propelled by her readings of Futurism, Dadaism and Surrealism. By 1980, she was affiliated with Just Above Midtown (JAM), the Black avant- garde gallery founded by Linda Goode Bryant, where artists such as David Hammons, Senga Nengudi, and Howardena Pindell were already active. O’Grady began by volunteering to work on communications for the gallery. It was during this time that she conceived of and first performed her landmark work Mlle Bourgeoise Noire (1980–83). “A critique of the racial apartheid still prevailing in the mainstream art world,” MBN saw O’Grady perform as the invented titular character whose unannounced “guerrilla” actions intervened in public art events. While she deemed the performance a failure due to its not having begun a meaningful integration of Black voices in the art world at the time, Mlle Bourgeoise Noire had a mythic aftermath that is felt to this day.

While honing her artistic voice O’Grady continued to write and publish. Her 1982 “Black Dreams,” featured in Heresies #15: Racism Is the Issue, was O’Grady’s first attempt to publicly engage with issues of Black female subjectivity. The essay employs personal anecdote and psychological description more than would her later writings which, though remaining accessible, gradually became more theoretical than narrative. In 1983, O’Grady, acting in her persona of Mlle Bourgeoise Noire, curated a group exhibit, The Black and White Show, at the Black-owned Kenkeleba Gallery, and staged her well-known performance Art Is… in Harlem. Both works continued her inquiry into the political and aesthetic complexities of an industry she experienced as persistently segregated. Her Central Park performance Rivers, First Draft (1982), alternated a second tendency of her work in this period, that of intense self-exploration. The work was a one-time only event with a cast and crew of 20, several of whom were part of JAM, including a young Fred Wilson and the late George Mingo. A “narrative three-ring circus of movement and sound” about a woman trying to become an artist, Rivers, First Draft simultaneously expressed the protagonist’s perspectives as a young girl, a teenager, and an adult woman. Its characters also symbolized conflicting aspects of O’Grady’s identity as both a native New Englander and the child of Black Caribbean parents. In 2015, she would re-imagine the work as a suite of 48 images displayed as a “novel in space.”

Over the course of the 1990s O’Grady’s voice became increasingly important to both the alternative New York art scene and mainstream artistic discourse. She was a member of the Women’s Action Coalition (WAC), to which she contributed a crucial intersectional viewpoint on feminist theory and praxis. In works such as Miscegenated Family Album (1980/1994), O’Grady synthesized history and identity, the personal and the political, by pairing photographic portraits of her family members with images depicting Ancient Egyptian figures such as Nefertiti and her relations. O’Grady, whose antecedents include enslaved persons, views Ancient Egypt as a “bridge” country, the cultural and ethnic amalgamation of Africa and the Middle East, which flourished only after its northern and southern halves were united in 3000 BC. The appropriation of the term “miscegenated” in conjunction with the use of ethnographic visual language poignantly addresses the hybrid experience of class, gender, and race across time. Through this lens, Miscegenated Family Album functions as a feminist opus whose goal is not to bring about a mythic “reconciliation of opposites” but rather to “enable or even force a conversation between dissimilars long enough to induce familiarity.” (. . . .)

Download full PDF

Career Narrative

Lorraine O’Grady (1934-2024) was a concept-based artist and cultural critic widely regarded as a leading intellectual voice of her generation. Working across media and disciplines––including writing, photography, performance, curating, installation, and video––O’Grady continued to challenge artistic and cultural conventions through her incisive critique of the binary logic inherent in Western thought. She skillfully deployed the diptych form to refute and subvert both the “either/or” logic of Western philosophy and, by extension, the prevailing understanding around gender, race, and class. Over the course of her career, she advocated for an anti-hierarchical approach to difference that follows the reasoning of both/and. From her earliest work, Cutting Out the New York Times (1977), to more recent series like Family Portraits (2020), O’Grady expanded the possibilities of conceptual art and institutional critique through her profound explorations of hybridism and multiplicity. And in writings such as “Olympia’s Maid: Reclaiming Black Female Subjectivity,” an influential essay of cultural criticism published in 1992, O’Grady continued to shape the theoretical contours of a body of work that has been groundbreaking in its charting of the emergence of Black subjectivity in both artistic modernism and Western modernity as a whole.

O’Grady came to artmaking in the late 1970s after having achieved professional successes as a research economist, a literary and commercial translator, and a rock music critic. Her decision to become an art maker being due to the desire to produce work in service of her own ideas, O’Grady has stated that art “is the primary discipline where an exercise of calculated risk can regularly turn up what you had not been looking for.” Indeed, O’Grady’s strategies in Cutting Out the New York Times (1977) were propelled by her readings of Futurism, Dadaism and Surrealism. By 1980, she was affiliated with Just Above Midtown (JAM), the Black avant- garde gallery founded by Linda Goode Bryant, where artists such as David Hammons, Senga Nengudi, and Howardena Pindell were already active. O’Grady began by volunteering to work on communications for the gallery. It was during this time that she conceived of and first performed her landmark work Mlle Bourgeoise Noire (1980–83). “A critique of the racial apartheid still prevailing in the mainstream art world,” MBN saw O’Grady perform as the invented titular character whose unannounced “guerrilla” actions intervened in public art events. While she deemed the performance a failure due to its not having begun a meaningful integration of Black voices in the art world at the time, Mlle Bourgeoise Noire had a mythic aftermath that is felt to this day.

While honing her artistic voice O’Grady continued to write and publish. Her 1982 “Black Dreams,” featured in Heresies #15: Racism Is the Issue, was O’Grady’s first attempt to publicly engage with issues of Black female subjectivity. The essay employs personal anecdote and psychological description more than would her later writings which, though remaining accessible, gradually became more theoretical than narrative. In 1983, O’Grady, acting in her persona of Mlle Bourgeoise Noire, curated a group exhibit, The Black and White Show, at the Black-owned Kenkeleba Gallery, and staged her well-known performance Art Is… in Harlem. Both works continued her inquiry into the political and aesthetic complexities of an industry she experienced as persistently segregated. Her Central Park performance Rivers, First Draft (1982), alternated a second tendency of her work in this period, that of intense self-exploration. The work was a one-time only event with a cast and crew of 20, several of whom were part of JAM, including a young Fred Wilson and the late George Mingo. A “narrative three-ring circus of movement and sound” about a woman trying to become an artist, Rivers, First Draft simultaneously expressed the protagonist’s perspectives as a young girl, a teenager, and an adult woman. Its characters also symbolized conflicting aspects of O’Grady’s identity as both a native New Englander and the child of Black Caribbean parents. In 2015, she would re-imagine the work as a suite of 48 images displayed as a “novel in space.”

Over the course of the 1990s O’Grady’s voice became increasingly important to both the alternative New York art scene and mainstream artistic discourse. She was a member of the Women’s Action Coalition (WAC), to which she contributed a crucial intersectional viewpoint on feminist theory and praxis. In works such as Miscegenated Family Album (1980/1994), O’Grady synthesized history and identity, the personal and the political, by pairing photographic portraits of her family members with images depicting Ancient Egyptian figures such as Nefertiti and her relations. O’Grady, whose antecedents include enslaved persons, views Ancient Egypt as a “bridge” country, the cultural and ethnic amalgamation of Africa and the Middle East, which flourished only after its northern and southern halves were united in 3000 BC. The appropriation of the term “miscegenated” in conjunction with the use of ethnographic visual language poignantly addresses the hybrid experience of class, gender, and race across time. Through this lens, Miscegenated Family Album functions as a feminist opus whose goal is not to bring about a mythic “reconciliation of opposites” but rather to “enable or even force a conversation between dissimilars long enough to induce familiarity.” (. . . .)

Download full PDF

Brief Bio

Lorraine O’Grady (1934-2024) was a conceptual artist and cultural critic whose work over four decades employed the diptych, or at least the diptych idea, as its primary form. While she consistently addressed issues of diaspora, hybridity and black female subjectivity and emphasized the formative roles these have played in the history of modernism, O’Grady also used the diptych’s “both/and thinking” to frame her themes as symptoms of a larger problematic, that of the divisive and hierarchical either/or categories underpinning Western philosophy. In O’Grady’s works across various genres including text, photo-installation, video and performance, multiple emotions and ideas coexist. Personal and aesthetic attitudes often considered contradictory, such as anger and joy or classicism and surrealism, are not distinguished. Even technical means seem governed by both chance and obsessive control so as to express political argument and unapologetic beauty simultaneously. And across the whole, essays and images interpenetrate. While O’Grady’s diptychs are sometimes explicit, with two images side by side, at other times they are implicit, as when two types of hair—silk and tumbleweed, videotaped on the same scalp at different hours of the same day—alternate and interact to create permeating worlds. The goal of her diptychs is not to bring about a mythic “reconciliation of opposites,” but rather to enable or even force a conversation between dissimilars long enough to induce familiarity. For O’Grady, the diptych helped to image the kind of “both/and” or “miscegenated” thinking that may be needed to counter and destabilize the West’s either/or binary of “winners or losers,” one that is continuously birthing supremacies, from the intimate to the political, of which white supremacy may be only the most all-inclusive.

An early adopter of digital technology, O’Grady also created a website, log-update.nbtechnologies.net, which is considered a model of the online abbreviated-archive, and her paper archive is in the collection of the Wellesley College Library. Among O’Grady’s writings, the 1992/94 long-form essay “Olympia’s Maid: Reclaiming Black Female Subjectivity” has proved an enduring contribution to the fields of art history and intersectional feminism and is now considered canonical. O’Grady’s art works have been acquired by, among other institutions, the Art Institute of Chicago. IL; Museum of Modern Art, NY; Tate Modern, London, UK; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA; and the Whitney Museum of American Art, NY.

Download full PDF

Early Work Experience Bio

MY JOB HISTORY

(a feminist “retrospective”)

© Lorraine O’Grady 2004

IT BEGAN as an interview for a student paper. . . .

Thu, Sep 23, 2004 16:42

Hey Grama Rain

For my Labor study: Women and Work, I have to interview 3-5 of my female family members and write a report on each, and I would like you to be one of them. These are the questions:

~What kinds of paid jobs have you held, approximately how old were you when you held them and what work did they entail? (in school and as an adult)

~What concerns if any, did you have in any of these jobs about working conditions, wages, benefits, hours, relationship to family responsibilities, sexual harassment, etc.?

~Was there any resistance within your family to you holding any of the jobs?

~Why did you choose these jobs?

Thanks so much. If you don’t have the time to answer the questions its ok i know your a busy lady, but i would be so grateful if you did. My paper is due the 30th next week so i need it before then. Thanks again

C.

Thu, Sep 23, 2004 21:33

Wow, C., that’s a tall order. You have no idea how many jobs I’ve had! I’ll do my best to get it to you by late Monday.

Grama Rain

Sun, Sep 26, 2004 23:16

Hey, C.,

I finished it a little early. It’s almost 9 single-spaced pages and only takes me up to 1972 (with a couple of flash-forwards to about 1990). I enjoyed writing it, and I even learned a few things. I didn’t specifically answer your questions, I had to ground them in the overall picture. But somewhere in there, I’m sure you’ll find stuff you can use for your paper. Hope you get a good grade!

Grama Rain

Mon, Sep 27, 2004 8:12

Thank you soooooo much! Wow that’s a lot of info. I better get started. I’ll let you know how i do.

C.

————————————————–

IN THE END, C. forgot to tell me her grade. I only recently learned that she’d received an A.

As for me, I ran out of time and energy at about 1972. I did a few flash-forwards but didn’t mention being a rock critic, and hardly discussed being an artist. One of these days, I’ll put down the whole story….

————————————————–

My First Job

When I started college in 1951, I was going to major in History. But after a course in Central European history, I knew I’d never be able to read fast enough. I couldn’t stop sub-vocalizing! So I decided to major in Spanish Literature. But after I got married and had a baby, I realized I would have to get practical. So I switched to Economics because I thought that would give me better job prospects. In my senior year, I went on a few interviews through the Career Center at Wellesley. But they weren’t too interesting. In those days, it seemed like the majority of recruiters, even at a high prestige women’s college like Wellesley, were fashion retailers. I went through the motions. I got dressed up, took the train to New York and talked with the people at Bergdorf’s and Alexander’s (opposite ends of the fashion scale). But it was clear, women retail buyers could only go so high. You would spend most of your life in dreary back rooms on the store floors, talking to low-level vendors with carpet fleas biting your legs.

That’s when I decided my training and interests were best suited for work in the government. It was the only “equal opportunity” employer at the time and, amazingly, it paid better than any of the other jobs. You took an exam and if you passed, you were in, even if you were a black female. This was 1956, and at that time, the Federal Government had an elite entry program called the (. . . .)

Download full PDF